Trial of 50c Public Transport Fares

Is the six-month trial of 50c fares for public transport in Queensland a clever strategy for change or a political stunt? Either way, what will it achieve?

Perhaps the best thing about the six-month trial of 50c fares in Queensland is that it has got more people talking about public transport. Reactions vary from delight at how much they will save, to complaints about not being able to benefit, to accusations that it’s a vote-buying exercise.

While these arguments are unlikely to change many minds, they provide valuable insights into attitudes towards different transport modes, the underlying economic mindsets, and how words and statistics can be misleading.

Subsidy or Investment?

Some simple Queensland government figures on the increase in the current subsidy per trip were provided in this ABC news story: Queensland's 50-cent public transport trial begins

Money spent on public transport is portrayed as a subsidy - a cost to all taxpayers to benefit the subset of the community who use public transport.

This feeds emotive public commentary like the Linkedin post below. Despite creating his own graph to imply some factual analysis and authority, the projected amount per trip in 2024 of $29.50, this becomes “easily over $30”.

Thanks to ABC News online for yesterday publishing the Qld Govt figures on both trains and buses, which I have graphed here. Keep in mind this is before the loss of fare revenue due to the 50c trial. Which means the taxpayer subsidy per person, per trip (ie per direction) is now easily over $30 each way for trains, or $60 a day round trip or $300 per week per traveller. Buses are much much less expensive and they carry more people across the region. https://www.linkedin.com/posts/ross-elliott-576b3217_wow-i-was-interviewed-on-steve-austins-activity-7226350184559960064-PRbu

The conflicting interests are set up - the taxpayer paying out versus the traveller getting an unearned bonus of $300 per week. This narrow and simplistic linear model excludes all of the external costs and benefits of each transport mode, including the invisible private car. Nowhere is the subsidy to private car use and storage even acknowledged.

Indeed, the language used by politicians and other proponents for building roads speaks of saving drivers from stopping for red lights and saving a few minutes on a journey but somehow isn’t a burden to the taxpayer. The justifications and “business cases” for the eye-watering sums proposed for a road tunnel under Gympie Road, show this massive double-standard and perpetuates the myth that roads are “investments” and reinforces the car dominance of our region.

Economics: Linear or Doughnut

In our society, the economics of transport is reduced to simple monetary values within a very narrow, blinkered framework. Assumptions are made to calculate the monetary value of commuter time in traffic. There is no recognition of the health, social, environmental, or cultural benefits or costs to individuals or to wider society.

The only people of interest in this linear economic model are those who already have the choice to travel on one mode or another, principally workers commuting to the CBD. It’s simple: 2+2=4. Transport poverty is certainly not included in the equation.

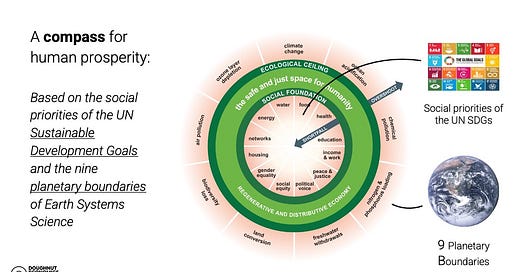

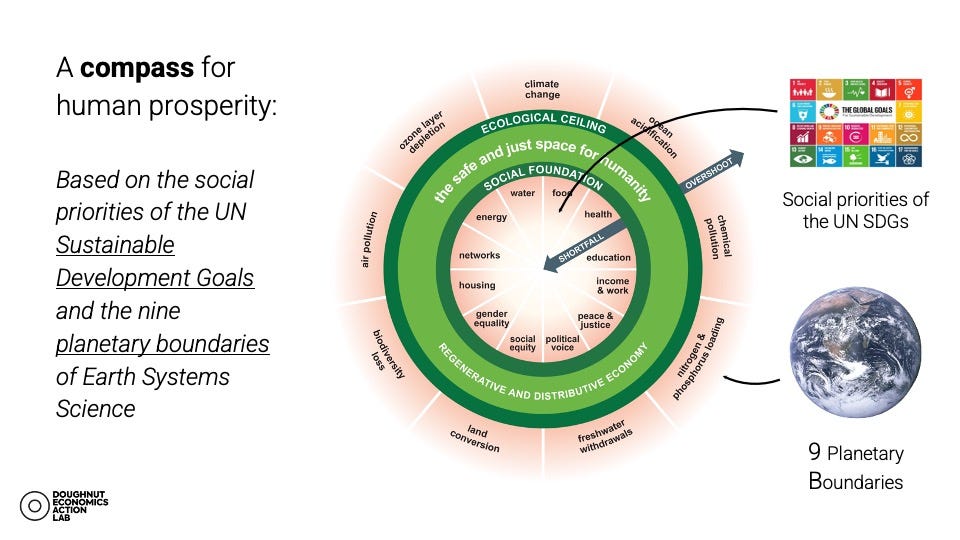

Now look at it from the Doughnut Economics perspective:

It’s much more complex when you look at transport systems though the Doughnut Economics framework; how much does each mode contribute to the overshoot, and how much do they support the social foundations.

If the fare price reduction moves some people from private cars to public transport, we may reduce some of the contributions to overshoot by reducing emissions. The reduced cost could possibly make work and education more accessible for some who already travel from outer suburbs. However, as many detractors pointed out, if you have no bus or train available, the fare is irrelevant. I find it hard to see any other significant benefits. If you can, please share them in the comments.

Better Questions

Using the doughnut model of measurement, we can compare all transport decisions, and the priorities and budgets allocated to each mode from walking to private car and everything in between, by asking:

How does this mode and all its associated infrastructure compare to others in each of the planetary boundaries: Air pollution, biodiversity loss, chemical pollution, water pollution, land conversion?

How does each decision benefit or detract from the social foundation? How might the choices of our transport system play a part in…

encouraging healthy, active lifestyles

increasing freedom for people of all ages and abilities to travel in safety and comfort to access their communities, services, employment, etc.

supporting independent lifestyles for all, including the many who don’t drive (age, income, illness, disability, etc.)

freeing parents and grandparents from needing to play taxi to children and teenagers

providing freedom from the financial burden of needing to own a car just to maintain employment

building community and neighbourhood networks

Evaluating the Success of This Trial

If discussion is reduced to people fighting over the crumbs of who gets the financial benefit of reduced fares, while ignoring the significant lack of transport options for the majority of residents and the financial strains caused by car dependency, when the six-month trial is over, what do you think will happen?

If one of the outcomes of the 50c fare trial is a broader public discussion on how we might transition to a fair and sustainable transport system for all residents, that could count as a success.

If that discussion stimulates the demand and transition to a better transport system that serves all community members, the environment, and the economy, the success would be ongoing.

How can we measure those outcomes in dollars? Should we even try?

I really like this Gayle and those are definitely better questions! I love to talk about circular economy but actually I think Doughnut Economics is more complete as a lens through which to analyse things isn’t it?

This definitely cements the power of the doughnut model for assessing options and opportunities. We need to increase the use of this model for more of the wicked problems we face.